A. OLD TESTMENT CANONS

What is the Old Testament?

The Bible as a whole, and the Tanakh (old Testament) in particular, reflects the truism that the Davar Elohim (Word of God) may be conveyed in many literary forms:

- 1. Historical narrative;

- 2. Poetry;

- 3. Prophetic exhortation;

- 4. Wisdom sayings; and

- 5. Edifying stories.

A consequence of this is that emet (truth) is presented and expressed in a variety of ways that is a reflection of the way that humans have been created, the most obvious being the difference between the left and right halves of the brain. Scripture therefore, like the human mind itself, appeals to different combinations of the analytical/methodical (left-brained) and the more creative or artistic (right-brained), one or the other of which tends to dominate in any one particular individual. For this and other reasons, people tend to gravitate toward the different literary forms in search of inspiration and edification, and therefore to different sets of Scripture books. Taken as a whole, Scripture reflects the interest and concern of the Creator as both Scientist and Artist for His children. Every kind of person has been catered for.

Jewish Tanakh Canon

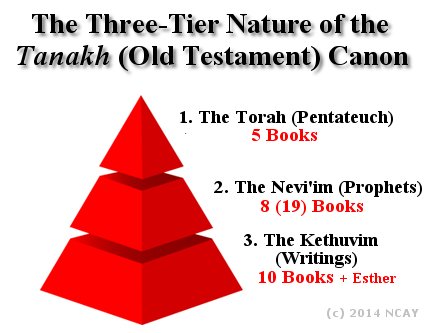

Over the course of time and since their arrival, scholars and scriptorians have tended to group or arrange the books of the Tanakh in different ways and orders. You'll find this discussed in materials about the Canon in this section. An examination of a Jewish or Messianic Tanakh alongside a Protestant Old Testament will immediately reveal differences. Indeed, the Jewish word 'TaNaKh' itself reflects that difference, being an acronym of the three collections of Scriptures of Torah (Pentateuch), Nevi'im (Prophets) and Kethuvim (Writings) arranged in the understood order of importance and (in the minds of many like ourselves), authority:

Two of these are traditionally sub-divided further:

- 1. Torah (Law)

- 2. Nevi'im (Prophets)

- a. Former Prophets

- b. Latter Prophets

- 3. Kethuvim (Writings, Hagiographa)

a. Poetical Books

b. The Megilloth (5 Rolls)

c. Historical Books

Protestant Old Testament Canon

Protestants have created five groupings based on similar criteria but have a peculiar grouping of the prophetic books based largely on their length (rather like the Suras of the Quran which are puzzlingly arranged exclusively on the basis of the length rather than on any chronology or theme) and the perceived importance or impact of the individual prophets themselves:

- 1. 5 Books of the Law (Genesis-Deuteronomy)

- 2. 12 Books of History (Joshua-Esther)

- 3. 5 Books of Poetry, Wisdom and Praise (Job-Song of Solomon)

- 4. 5 'Major' Prophets (Isaiah-Daniel)

- 5. 12 'Minor' Prophets (Hosea-Malachi)

Catholic Old Testament Canon

Catholic Bibles, which include the Apocrypha (as indeed do many Bible translations used by both Protestant and Catholic communities such as the New Revised Standard Version), arrange the Old Testament slightly differently (Aprocryphal books are coloured):

- 1. Pentateuch (Law, Torah)

- 2. Historical Books (Joshua-Nehemiah)

- 3. Biblical Novellas (Tobit [~200 BC], Judith [~150 BC], Esther (plus Apocryphal additions [~140-130 BC]), 1 & 2 Maccabees [~170-110 BC])

- 4. The Wisdom Books (Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Wisdom [30 BC], Ben Sira [132 BC])

- 5. The Prophetic Books (including some Apocryphal additions to the Book of Daniel - Prayer of Azariah [~200 BC], Song of the Three Holy Children [~200 BC], Story of Susanna [~200 BC], Bel and the Dragon [~100 BC], and additions to Baruch with the Letter of Jeremiah [~150-50 BC]).

Eastern Old Testament Canons

The further east you go in Christendom, the more apocryphal and pseudeprahical books appear in their Old Testament canons. If you're interested in reading these as well as the Catholic Apocryphal editions, get a copy of the scholars' Bible, the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) which includes them all:

A. Eastern Orthodox

B. Syriac Orthodox

- 1. 2 Baruch + Letter of Baruch (only the Letter is canonical)

- 2. Psalms 152-155 (not canonical)

C. Ethiopian Orthodox

- 1. 4 Baruch (Paralpomena of Jeremiah)

- 2. 1 Enoch

- 3. Book of Jubilees

- 4. 1, 2 & 3 Ethiopian Maccabees

- 5. The Ethiopian 'Broader Canon'

Summary of Canons

The chart belows gives a summary of the various denominational canons of the Tanakh or Old Testament. It lists the books of the Old Testament, showing their position in both the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible, shown with their names in Hebrew) and Christian Bibles. The Deuterocanon is shown in yellow and the Apocrypha in grey and are not accepted by most Jews and Protestants. The Protocanon is shown in red (the Samaritan Canon as well as the Canon of the historical Sadducees), orange, green and blue which are considered canonical by all the major denominations. Messianic denominations are diverse in the canons which they accept.

For historical reasons, and in order to maintain unity, Messianic Evangelicals limit themselves to the Jewish/Protestant canon of the Tanakh/Old Testament. We do, however, consult non-canonical books for historical purposes. The reasons why are explained in materials in this section.

B. HOW TO ACCEPT & USE THE OLD TESTAMENT

The Believer's Primary Book of Scripture

It has been wisely proclaimed that if you do not understand the Tanakh (Old Testament), your understanding of the Messianic Scriptures (New Testament) will be distorted. Messianic Evangelicals fully agree. Most Christians are unaware that for the first 300 years of the Messianic/Christian era there was no 'New Testament', and though Christian writings in the form of gospels, histories and letters started circulating from as early as the 50's AD, for at least the first 20 years of the Messianic Community (Church), if not longer, the Tanakh (Old Testament) was "the Scriptures" (Mt.21:42; 22:29; 26:54,56; Mk.12:24; 14:49; Lk.24:27,32,45; Jn.5:39; Ac.17:2,11; 18:24,28; Rom.15:4; 1 Cor.15:3-4; 2 Pet.3:16), and exclusively so.

The Authority Given the Tanakh by Messiah

Whenever the Messianic Scriptures (New Testament) speak of "the Scriptures" it is only of the Tanakh (Old Testament) and never what we call the 'Bible' today. Indeed, not only did the writers of the Gospels, Letters, Apocalypse, etc., have no idea that their writings would one day become 'Scripture' but nowhere in either Old or New Testament is any prophecy ever made predicting the coming forth of a 'Bible', whether with or without a 'New Testament' section, hard though many Christian apologists have tried to force them into saying such a thing. Nevertheless, it is clear that the Tanakh (Old Testament) possessed an authority that was, critically, acknowledged by the Messiah Himself. On this basis alone we should accept it.

How Christ Viewed the Tanakh

In answering the valid and important question posed to Him once by a parishoner as to how the Old Testament should be accepted and used today, we consider no better counsel to have been given than by the late Anglican Bishop, F.J.Chavesse, in 1927 in Liverpool, England, who replied:

"Accept it as Christ accepted it. Use it as Christ used it - as His Manual of Devotion, His Armoury for the Defence of Truth, and His Final Court of Appeal."

How the New Testament Acquired Its Authority Relative to the Old

As the Tanakh (Old Testament) acquired its original authority from the nevi'im (prophets), the Priesthood, and then the Israelite community as a whole through common usage, so the same may be said of the Messianic Scriptures (New Testament). And though the 'Spirit' is usually invoked for the existence of the 'New Testament' as authoritative and canonical for our use today - as the invisible proxy of the resurrected Christ - its authority and canon has frequently been questioned by important leaders like Martin Luther and other spiritual movers over the centuries especially when it has seemed to endorse the Old Testament Torah or Law. Nevertheless, all attempts to reduce New Testament canon (as Luther tried) or add to it seem to have been consistenly resisted, in spite of recent attempts by some messianics to cut out Hebrews or the writings of Paul because these contradict some of their own doctrines.

The New Testament as a Continuation and Completion of the Old

Though we obviously have no recorded statement made by Christ endorsing the New Testament as we do the Old, the fact that the New Testament has survived 2,000 years' worth of attempts by some to modify its canon strongly suggests to nearly the entire Christian/Messianic Community that what we have is bona fide Scripture. Nevertheless this does leave the Tanakh (Old Testament) in an indisputably higher position of authority as the primary work of Yahweh, our Heavenly Father, upon which has been built, as a work of continuation, the Witness of the Son in the Gospels and elsewhere, followed by that of the Apostles who knew Messiah in the flesh, and finally by the witness of the Apostle to the Gentiles, Paul. Thus for Messianic Evangelicals, there is both an hierarchy of Testaments (Old before the New) as well as an internal hierarchy of collections of each Testament's books, based on the principle of later revelation building upon earlier revelation and never contradicting it. This way the Body may be protected from the bane of false doctrine that often emerges when scriptural hierarchies are disregarded.

The Hierarchy of the Bible Parts

Thus the Gospel of Christ the Son is first and foremost the Gospel of Yahweh-Elohim (God) the Father, not the gospel of Paul, Apollos or Cephas (Peter) (1 Cor.3:21-22). If Christ was submitted to the Tanakh (Old Testament) and used it as His manual of devotion, His armoury for the defence of doctrinal emet (truth), and His final court of appeal, then so should Christians/Messianics in imitation of their Saviour. The importance and worth of the Tanakh (Old Testament) then becomes beyond estimation since it defines, amongst other things, the required believer's lifestyle in every dispensation. That which the New Testament, by its very nature, completes cannot therefore be replaced, disregarded or subordinated, any more than the teachings of Christ in the Gospel can be subordinated by the teachings of Paul. The later revelators can only amplify.

A Single Book of Scripture

The Elohim (God) of the Tanakh (Old Testament) is the same as the Elohim (God) of the New. There aren't two different Gods, as the ancient heretical sect of Gnostics taught, and as some today falsely accuse directly or by implication, a reason that the Tanakh (Old Testament) must always lead as the first three Acts of Elohim's Divine Play or Story. It is not, however, by itself, a complete revelation and requries the New Testament for its goal to be fully understood. There is therefore a mutual, synergistic dependence. The Old and New Testaments are a single Story, and therefore must be properly viewed as One Book to which the final Acts and Scenes will one day be added when Messiah returns.

C. THE DIVISIONS OF THE TANAKH

a. The 'Pentateuch' or 'Torah'

The first five books of the Tanakh (Old Testament) and Bible as a whole or 'Pentateuch' (Gk. penta = 5) - Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy (or simply 1-5 Moses) - were, and are, the original or core Torah (meaning Law, Teaching) although the term 'Torah' has subsquently come to be applied muchy wider to:

- 1. The Pentateuch;

- 2. The whole Tanakh (Old Testament); and

- 3. The whole Bible (Old and New Testaments).

The Pentateuch (1-5 Moses) is central to the Sinai Covenant and the legislation mediated through the navi (prophet) Moses.

Genesis, the Opening Story

These five books of Moses form a unity telling a single story, beginning with the creation and destining mankind for the blessings of progeny and land possession (Gen.1-3). As the human race expands, its evil conduct provokes Yahweh to send a universal flood to wipe out all but righteous Noah's family. Once the flood had subsided, the planet is repopulated from his three sons, Shem, Ham and Japheth (Gen.4-9) and from these families are descended the 70 nations of the civilised world whose offense this time - building a city rather than taking their assigned lands (Gen.10-11) - provokes Yahweh to elect one family from the rest. Abraham and his wife Sarah, landless and childless, are promised a child and the land of Canaan. Amid trials and fresh promises, a son (Isaac) is born to them and Abraham takes title to a sliver of Canaanite land as a kind of downpayment for later possession (Gen.12-25). Genesis 25-36 tells how their descendant Jacob becomes the father of 12 sons through his 4 wives (because of which he is renamed 'Israel'), and Genesis 37-50 tells how the rejected brother Joseph saves the family from famine and brings them to Egypt.

Exodus from Slavery

In Egypt, a Pharaoh did not know Joseph, subjects the '70 sons of Jacob' or 'Hebrews' to slave labour, keeping them from their land and destroying their male progeny (Ex.1). Moses is commissioned to lead the people out of Egypt to their own land (Ex.2-6). In 10 plagues, Yahweh defeats Pharaoh and the gods of Egypt. Free at last, the Hebrews leave Egypt and journey to Mount Sinai (Ex.7-18), where they enter into a covenant to be the people of Yahweh and be shaped by the 10 Commandments and other torot (laws) (Ex.19-24). Though the people commit apostacy when Moses goes back to the mountain for the plans of the Tabernacle, Moses' intercession prevents the abrogation of the covenant by Yahweh (Ex.32-34). An important principle has been established, however: even the people's rebellion and apostacy need not end their relationship with Elohim (God) provided there is repentance. The book ends with the cloud and the glory taking possession of the tent of meeting (Ex.36:34-38). "The sons of Israel" in Exodus 1:1 are the actual sons of Jacob/Israel the patriarch, but by the end of the book they are the nation Israel, for all the elements of nationhood in antiquity have been granted: a Deity, a Temple, a Leader and an authoritative tradition.

Leviticus & Numbers

Israel remains at the qadosh (holy, set-apart) mountain for almost a year. The entire block of material from Exodus 19:1 to Numbers 10:11 is situated at Sinai. The rituals of Leviticus and Numbers are delivered to Moses at the qadosh (holy, set-apart) mountain, showing that Israel's worship tavnith (pattern) was instituted by Elohim (God) and part of the very fabric of the people's life. Priestly material in Exodus 25-31 and 35-40 describes the basic institutions of Israelite worship (the tabernacle, its furniture, and priestly vestments). Leviticus, aptly called in rabbinic tradition the 'Priests' Manual', lays down the rôle of cohenim (priests) to teach Israel the distinction between kosher (clean) and unkosher (unclean) and to see to their holiness. In Numbers 10:11-22:1, the journey is resumed, this time from the Sinai through the wilderness to the Transjordan - Numbers 22:2-36:16 tells of events and laws in the plains of Moab.

Deuteronomy - the Four Sermons of Moses

The final book of the Pentateuch, Deuteronomy, consists of four speeches by Moses to the people who have arrived at the plains of Moab, ready to conquer the land:

- Speech #1: Dt.1:1-4:43;

- Speech #2: Dt.4:44-28:68;

- Speech #3: Dt.29:1-32:52; and

- Speech #4: Dt.33:1-34:12

A Uniquely Called People

The Pentateuch witnesses to a coherent story that begins with the creation of the world and ends with Israel taking its land. The same story is repeated in the historical parts of the Psalms (Ps.44; 77; 78; 80; 105; 114; 149) and in the confessions of Deuteronomy 26:5-9, Joshua 24:2-13 and 1 Samuel 12:7-13. Though the narrative enthralls and entertains, as all great literature does, it must be remembered that it is a theopolitical charter or covenant as well, meant to establish how and why descendants of the patriarchs are a uniquely qadosh (holy, set-apart) people among the world's nations.

b. The Historical Books

From Joshua to Exile

After the Pentateuch comes a series of books that continue, in roughly chronological order, the history of Israel. Joshua depicts Israel taking possession of the land of Canaan. Judges collects stories about the leaders of early Israel in the 200 years before the emergence of the monarchy. After the story of Ruth, a kind of interlude in the narrative sweep of these books, 1 & 2 Samuel tell of the rise ans fall of Saul, Israel's first king, and the succession and success of David. The two books of Kings (a single volume in the Hebrew Tanakh) take us from the death of David and the enthronement of Solomon, through the division of the people into the two kingdoms of Israel (northern) and Judah (southern), to the destruction of the Northern Kingdom of Israel at the hands of the Assyrian invader (722/721 BC), and the fall of the Southern Kingdom of Judah, to the Babylonians (587 BC) and its ensuring exile, the Babylonian captivity.

Chronicles, Ezra & Nehemiah

The two books of Chronicles (also a single volume in the Hebrew Tanakh) recycle much of the material found in the previous works, but the unknown author ('the Chronicler') treats it selectively, with a characteristic emphasis on the Temple and its operation, which by way of legitimation are attributed to David, the ideal king. The Chronicler's interests carry through the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, which recount the restoration of Yehudi (Judahite) worship and life in the period of Persian rule following release from the exile in Babylon.

The Intertestamental Interlude

The books of Maccabees, though not Scripture, are useful overlapping (though somewhat contradictory) historical accounts of Yehudi (Judahite) resistance to Seleucid persecution in the early 2nd century BC and the assumption of power by the leaders of the resistance, the Maccabees or Hasmoneans. These books do not appear in the Hebrew or Protestant canons, on account of their uninspired nature, leaving an historical gap between the Old and the New Testaments. This timeframe is useful in giving us a solid historical and theological context for the New Testament which is why Messianic Evangelicals lay great importance in studying this period.

Why So Much Historical Narrative

Christians/Messianics often wonder why there are so many historical materials in what is, after all, supposed to be a religious book, and the answer is that theology is never purely abstract but incarnational. Christianity is an historic faith, its central event - the resurrection - upon which the future of mankind depends, is rooted in space and time. History is important for many reasons, not least of which is because Christianity is not a myth, unlike most other religions. Excluding myths from the narrative, save where it is clearly meant to be read parabolically, therefore becomes of critical importance to the validation of the faith.

c. The Novellas

Inspired or Uninspired Fiction?

Unfortunately, as we saw above, some myths have crept into the various Old Testament canons of the various churches. These are yarns or fairy tales, relating events which never took place, and whilst some like the Catholics insist these are edifying stories, this is not usually the view of Judaism and Evangelical Christianity. The books of Tobit, Judith (both found in the Catholic Apocrypha), and Esther are often grouped together. They are included in the Catholic canon because of the belief by that institution that they are profitable for instructing believers concerning the ways of Elohim (God). It is for this reason that the Book of Esther is likewise retained by Protestants even though, as we shall see, this is most likely only partly historical, and was not included in the canon of the oldest Old Testament canon that we know of, that which comprised the Dead Sea Scrolls found at Qumran. All three books are therefore works of fiction.

The Apocryphal Book of Tobit

Tobit was written in the 2nd century BC and is the story of a devout family in 7th century Assyria. The unknown author gives the people of his own time an example to follow as they struggle with the tensions of living a faithful Jewish life in the midst of a non-Israelite civilisation. Tobit, suffering from the affliction of blindness, perseveres in good works and prayer, as do other characters in the story. Elohim (God) sends a malak (angel) who, while hidden from them, leads them to health and happiness. The conclusion demonstrates that God does answer prayer and that perseverence in good works does not go unrewarded.

The Apocryphal Book of Judith

There are numerous clues in Judith proving it is not an historical text. All the worst enemies of the people - the Assyrians of the 8th and 7th centuries and the 6th century Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar, are all rolled into one terror. The heroine, Judith, is modelled on the heroes of the Book of Judges, yet her story is also reminiscent of a 2nd century hero, Judas Maccabeus (1-2 Maccabees). Even the conflation of time indications - the 18th year of Nebuchadnezzar (Tobit 2:1, the year 587 BC, when he destroyed Jerusalem and took the Judeans into exile) with the return from exile and rededication of the Temple (Tobit 4:3; the events of 538 and 515, respectively) - suggests Elohim's (God's) deliverance from the most terrible circumstances. The story is set in a time long past but it is meant to encourage the people of the late 2nd century BC to trust in Elohim (God) when their way of life is threatened. Elohim (God) can use even the most unlikely means, such as a widow, a biblical figure of powerlessness and vulnerability, to deliver them from their enemies.

The Esther Fable

The book of Esther does include several historical elements. The Persian king Xerxes (486-465 BC), the city of Susa, and a court official named Marduka, are all known from other sources. But further investigation shows that Esther is not meant to be an historical account. There is no record of Xerxes having any other queen than Amestris and no mention of such a massacre during his reign. The story of the book, though fictional, was created to provide an historical basis for the extra, non-Torah festival of Purim, which is not observed by Messianic Evangelicals precisely because it is fictional, its observance is nowhere commanded by Yahweh through a navi (prophet), and because it has been used - and still is used - as a justification for racial violence and genocide. Purim was originally a pagan Persian feast. And whilst it may be argued that through the story of Esther, Purim becomes a celebration of Elohim's (God's) rescue of the people from persecution and certain death, it is our contention that the Bible already furnishes plenty of authentic stories based in historical fact that are more than adequate for the task. (For more information about Esther, see the PURIM website).

d. The Wisdom Books

'Wisdom Books' is a convenient umbrella term to designate the Books of:

- 1. Job;

- 2. Proverbs;

- 3. Ecclesiastes (Qoheleth);

- 4. Wisdom [of Solomon] (Apocrypha); and

- 5. Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) (Apocrypha)

to which we would be justified in adding two other books:

- 6. Psalms, a collection of mostly devotional lyrics (though containing some important prophetic material too); and

- 7. Song of Songs (or Song of Solomon or Canticles), a collection of love poems.

Didactic or Instructional Literature

All of these are marked by the skillful use of parallelism, or verses of balanced and symmetrical phrases. These works have been classified as wisdom or didactic literature, so-called because their general purpose is instruction. A striking feature of the wisdom books is the absence of references to the promises made to the patriarchs or to Moses, or to Sinai or typical items in Israelite tradition - the exceptions would be the two Apocryphal books, Sirach (ch.44-50) and Wisdom (ch.10-19). Biblical wisdom literature concentrates on daily human experience and asks the question: How is life to be lived? In this respect it resembles, in some ways, comparable ancient Near Eastern compositions from Mesopotamia and Egypt that also reflect on the problems of everyday life.

The Nature and Task of Wisdom

The literary style is wide-ranging: aphorisms (pithy observations containing a general truth), numerical sayings, paradoxes, instructions, alphabetical and acrostic poems, lively speeches, etc.. Wisdom itself is an art: how to deal with various situations and achieve a good life. And it is also a teaching: the lessons garnered from experience were transmitted at various levels, from education in the home all the way to training in the court. Belief in Yahweh and acceptance of the prevailing codes of conduct were presupposed - they fed into the training of youths. The task of wisdom is character formation: what is the wise path to follow? The lessons are conveyed by observations that challenge as well by admonitions that warn. Although the need of discipline is underlined, the general approach is persuasion. The pursuit of wisdom demands more than human industry. Paradoxically, it remains the gift of Elohim (God) (Prov.2:6). Its religious character is indicated by the steady identification of wisdom and virtue (e.g. Prov.10-15).

Wisdom as Female

But wsidom is far more than a practical guide. The strongest personification in the Bible is 'Woman Wisdom' on the human level, and the Ruach haQodesh (Holy Spirit) on the divine level. Accordingly, she speaks somewhat mysteriously in divine accents about her origins and identity. Her appeal to humanity is sounded in several books (Prov.8; Sirach 24; Wisdom 7-9; Baruch 3:9-4:4). She offers "chayim (life)" to her followers. This image of personified Wisdom is further reflected in the Davar/Logos poem of John 1:1-18 and in Paul's reference to Yah'shua (Jesus) as "the wisdom of Elohim (God)" (1 Cor.1:24,30) where the Son takes the subordinate ('female') position with respect to the Father ('male'). The bearing of wisdom literature on the Messianic Scriptures (New Testament) is also exemplified in the sayings and parables of Yah'shua (Jesus) and in the practical admonitions in the Epistle of James.

Proverbs, Canticles, Job & Psalms

Each book has a distinctive character. Proverbs consists of long poems dealing with moral conduct (Prov.1-9), which introduce collections of aphorisms (Prov.10-29) reflecting on the experiences of life. Job is a literary presentation of the problem of suffering of the innocent and god-fearing Job. Psalms, the book of prayer par excellence, derives from various origins, especially liturgical celebrations of the divine moedim (appointments): it contains cries of agony as well as praise and thanksgiving. Some psalms betray a wisdom influence (e.g. Ps.37) and the very first Psalm serves as an invitation to learn about the ways of the just and wicked in the rest of the psalter.

Ecclesiastes, Wisdom & Sirach

Ecclesiastes examines the hard questions of life, and has become famous for the expressive phrase "vanity of vanities". The Song of Songs is a collection of poems that give meaning to human and divine love (SS 8:6; Prov.30:18-19). Ben Sira is the only author who identifies himself (Sir.50:27), and around 300 BC he writes a compendium of Yehudi (Judahite) wisdom and creation theology. The Wisdom of Solomon was written in Greek against a Hellenistic background, affirming human immortality in terms of a continuing relationship with Elohim (God). Except for Psalms (of which almost half are attributed to David), Job, and Sirach, the books are attributed to Solomon, probably on account of his fame as a wise man (1 Ki.5:9-14; 10:1-10), but there are undoubedly many other sages who have contributed to this body of literature. Some were found in ordinary families (father, mother, Prov.1:8; 10:1), others were scribes at court. All contributed, both men (the counsellors of Absalom - 2 Sam.16-17; the men of King Hezekiah - Prov.25:1) and also women (the "wise woman" of Abel Beth-maacah - 2 Sam.20:16). Some of the wisdom literature is post-exilic in composition but the dating is only approximate.

The Megillot

In Jewish tradition, the Megillot (Scrolls) came to be the accepted term for the five books of Ruth, Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, Lamentations, and Esther.

e. The Prophetic Books

The prophetic books bear the names of 4 'major' and 12 'minor' nevi'im (prophets), in addition to Lamentations and Baruch:

- A. The 'Major' Prophets

- 1. Isaiah

- 2. Jeremiah

- 3. Ezekiel

- 4. Daniel

- B. The 'Minor' Prophets

- 1. Hosea

- 2. Joel

- 3. Amos

- 4. Obadiah

- 5. Jonah

- 6. Micah

- 7. Nahum

- 8. Habakkuk

- 9. Zephaniah

- 10. Haggai

- 11. Zechariah

- 12. Malachi

- C. Addenda

- 1. Baruch

- 2. Lamentations

The terms 'major' and 'minor' refer to the length of these books and not the relative importance of the nevi'im (prophets) themselves.

Jonah, Lamentations, Daniel & Baruch

Jonah is distinguished from the others for being a story about a navi (prophet) rather than a collection of prophetic pronouncements. In the Hebrew Tanakh, Lamentations and Daniel are listed among the Kethuvim or Writings (Hagiographa), not among the prophetic books. The former contains a series of laments over the destruction of Jerusalem by the Babylonians. The latter is considered to be a prophetic book, though it consists of a collection of 6 edifying diaspora stories (Dan.1-6) and 4 apocalyptic visions about the end times (Dan.7-12). Baruch is not included in the Hebrew canon, but is in the Septuagint (LXX) or Greek Version of the Bible.

The Ancient Prophet

The prophetic books contain a deposit of prophetic preaching, and several of them in addition are filled out with narrative about nevi'im (prophets) (e.g. Is.7; 36-39; Jer.26-29; 36-45; Amos 7:10-17). In ancient Israel a navi (prophet) was understood to be an intermediary between Elohim (God) and the community, someone called to proclaim the Davar Elohim (Word of God). Nevi'im (prophets) received such communications through various means, including visions and dreams, often in a state of transformed consciousness and transmitted them to the people as Yahweh's messengers through oracular utterances, sermons, writings, and symbolic actions.

How Prophetic Books Came to Be

It would be misleading to think of these works as books in our sense of the word. While some prophecies originated as written material, prophetic activity more commonly took the form of public speaking. Prophetic discourse addressed to different audiences in different situations would, typically, be committed first to memory, then to writing, often by the navi's (prophet's) followers, sometimes by the navi (prophet) himself (e.g. Is.8:1-4; Jer.36:1-2; Hab.2:2). Small compilations of such pronouncements and discourses would be put together, arranged according to subject matter (e.g. pronouncements against foreign nations), audience (e.g. Jeremiah to King Zedekiah - Jer.21:1-24:10), chronological sequence (but see Ezekiel's jumbled up scrolls), or by verbal association (e.g. catch-words). These units would be circulated, edited, expanded and interpreted as the need arose to bring out the contemporary relevance of older prophecies, and eventually integrated into larger collections. The titles would have been added at a later date, in some instances possibly centuries after the navi (prophet) in question.

The Office and Calling of Prophet

The office of navi (prophet) came about as the result of a direct call from Yahweh. Unlike that of the Levitical cohen (priest), the prophetic function was not hereditary and did not correspond to a fixed office. In Israel as elsewhere in the ancient Near East and Levant, there were, however, nevi'im (prophets) who were employed in temples and at royal courts, and some of the canonical nevi'im (prophets) may have started out as 'professionals' of this kind. Prophecy also differed from priesthood in ancient Israel in that there were both male and female nevi'im (prophets). Though none of the prophetic books is named for a neviah (prophetess), Miriam (Ex.15:20) and Deborah (Judg.4:4) played important rôles at the beginning of Israel's history and Huldah (2 Ki.22:14) toward the end.

Commissioning Prophets

The Bible gives great importance to the call or commissioning of a navi (prophet), which was often accompanied by visionary or other extraordinary experiences (e.g. Jer.23:21-22; Ezek.1-2). In these accounts the prophetic intermediary can be represented as a messenger commission by Yahweh as king (e.g. Micaiah in 1 Ki.22:19-23, and Isaiah in Is.6:1-13, and therefore prophetic speech is often introduced with the form used in the delivery of a message: "thus says Yahweh (the LORD)" or some similar formula. Sometimes the prophetic calling could be expected to involve struggle, persecution, and suffering.

Issues Addressed by Prophets

While prophetic messages sometimes bore on the future (foretelling), their primary concern was with contemporary events in the public sphere of social life and politics, national and international (forthtelling). They focus on public morality, the treatment of the poor and disadvantaged, and the abuse of power, especially of the judicial system. They pass judgment in the strongest terms on the moral conduct of rulers and the ruling class, in the belief that a society that does not practice justice and righteousness will not survive. With equal rigour they also condemn a religious formalism that would legitimate such a society (e.g. Is.1:10-17; Jer.7:1-15; Amos 5:21-24). They view international affairs, the rise and fall of the great empires, in the light of their own passionate belief in the Elohim (God) of Israel and the destiny of Israel. The nevi'im (prophets) never take political and military power as absolutes. They do not preach a new morality. They are radicals only in the sense of radical commitment to and interpretation of the religious, legal, and moral traditions inherited from Israel's past emerging from the Torah revelation.

Positive and Distant Prophecy

Prophetic speech is not, however, confined to judgment and condemnation. The nevi'im (prophets) also exhort, cajole, and encourage. They announce salvation and a good prognosis for the future. Sometimes present realities and situations shade off into, or are taken up into, a panorama of a more distant future.

D. Old Testament Authority

A Book Poitning to the Messiah

In the Tanakh (Old Testament) all authority is spoken of as belonging to Yahweh the Father, and then, in the era of the Messianic Scriptures (New Testament), that authority is revealed to have been delegated to Yah'shua the Messiah (Jesus Christ) the Son (Mt.28:18) for the duration of the age (æon) (1 Cor.15:24), and to whom all the Tanakh (Old Testament) prophecies point.

Does the Bible Possess All Authority?

In the minds of most Protestants the 'Bible' (Old and New Testaments) is the 'only authority'. This doctrine emerged in the Reformation 500 years ago to counter Catholic institutional abuses as an alternative to claimed Catholic institutional church authority: 'the Bible or the Catholic Church: choose', was the challenge. In modern times, a similar choice is offered: 'the Bible or secularism'. The suggestion that the Bible is, or contains, all authority then lays the believer vulnerable to the claims of its interpreters who then effectively become a gaggle of new 'popes' and mini-institutions. A reason, we suggest, the Bible books nowhere prophesy the coming together of a single book was to preclude this error from resulting in a different kind of idolatry to the ones roundly condemned by the nevi'im (prophets). Messianics too have the same idolatrous tendency to ascribe 'all authority' to the Torah.

To Avoid Inventing Other Messiahs

Messianic Evangelicals believe that the Tanakh and Messianic Scriptures are authoritative - Scripture does possess authority but this is said by us, and is, we believe, intended by Scripture itself, as a shorthand for 'the authority of Yahweh in Yah'shua (Jesus), mediated through Scripture'. As believers, we live under the authority of Yah'shua (Jesus) but it is only through the Bible as a whole - from Genesis to Revelation - that we can accurately know who Yah'shua (Jesus) is. Remove either Testament, diminish them or water them down, and man then becomes free to invent a 'Jesus', 'Yeshua', 'Yahshua', 'Joshua', 'Yehoshua', or Yahushua' of his own making, a 'messiah' a little bit different from the Yah'shua (Jesus) who is hidden in the Tanakh (Old Testament) and revealed in the Messianic Scriptures (New Testament).

For What Does Yahweh's Authority Exist?

All true believers live under the toqef or authority of the Tanakh (Old Testament) and Messianic Scriptures (New Testament) - the Bible - because that is the way we live under the authority of Elohim (God) that has been vested in Yah'shua the Messiah (Jesus Christ), our Master (Lord). But what is Yahweh-Elohim's authority there for? To establish His Kingdom on earth as in heaven, completing the work begun but aborted in Genesis 1-3. This is the 'big story' of which 'getting saved' is part - the most important part, to be sure, but not the only part. There is a larger, organic story to the purpose of Creation which gets lost if the New Testament becomes detatched from the Old and is preferantially or exclusively lit up by the Messianic Community (Church).

The Ultimate Purpose of the Authority

Elohim's (God's) authority, vested in Yah'shua the Messiah (Jesus Christ), is not just how to give believers accurate information about how to get saved, but is to provide information on how saved believers are supposed to life the Torah lifestyle mandated by the Creator from the beginning, the details of which are almost exclusively to be found in the Tanakh (Old Testament). But Yahweh's authority is ultimately even more than that: it is about Elohim (God) reclaiming His proper lordship over all creation. For as we learn in the Tanakh (Old Testament), the way Yahweh-Elohim planned to rule over His creation from the very beginning was through obedient humanity, a task that has yet to be accomplished, and for which we are being saved. The Bible's witness to Yah'shua (Jesus) declares that He, the Torah-obedient Man, has done this lordship reclamation viâ the Cross. The Bible - Old and New Testaments - is then the Elohim-given equipment through which the talmidim (disciples) of Yah'shua (Jesus) are themselves equipped to be obedient stewards, the royal priesthood (1 Pet.2:9), bringing that saving rule of Elohim (God) in Messiah (Christ) to the world.

Conclusion

These are the main reasons we study the Tanakh (Old Testament) alongside the Messianic Scriptures (New Testament) and why the former is indispensible. The articles in the register talk more about the Tanakh (Old Testament) itself and the rest of the website explains about the mission of the Bible and its contents as a whole.

(5 October 2019)

|