Most forms of 'Christian' or 'Messianic' Mysticism are but fronts for occultism and satanism. But is there what might be called a bona fide or authentic Christian or Messianic Mystical Tradition? And if so, what exactly is it?

Evidence of mysticism within early Christian literature is determined by the way in which the term is defined. The actual noun 'mysticism' (Gk. mysteriódia) occurs nowhere within these materials, but came into use only toward the end of the 5th century through the work of Pseudo-Dionysius (or Denys) the Areopagite, a Christian Neoplatonist who transposed in a thoroughly original way the whole of Pagan Neoplatonism - from Plotinus to Proclus, but especially that of Proclus and the Platonic Academy in Athens - into a distinctively new Christian-Pagan hybrid that is the bedrock of Catholicism and her offshoots.

Prior to this time, widespread use was made of the Latin contemplatio ('contemplation'), a term which continued to be popular within the Western (Roman) Church well into the Mediaeval period.

In its most general sense, ancient mysticism may be characterised both as the spiritual union of the human with the divine and as an introduction to some specific secret or mystery. It is in both of these senses that pagan Hellenistic mystery religions employed such concepts as 'mystery', 'mystical', and 'the mysteries'. Similar terminology quickly entered Christian vocabulary, but unlike pagan pantheistic religions, the idea of a personal Elohim (God) in biblical religion has restricted any true sense of 'unification' between human and divine.

The evidence strongly suggests that the dark currents of ancient movements such as Gnosticism, Jewish mysticism, Greek speculation, and Neoplatonic doctrine ultimately had great influence upon later Christian, and especially Catholic and Eastern Orthodox, views on mysticism.

The purely biblically-based view of mysticism, which Messianic Evangelicals strictly and exclusively adhere to, has maintained a special and separate quality from the occultism of the 'mystery religions' because of its entire focus upon the believer's union with the person of Yah'shua the Messiah (Jesus Christ) through emunah (faith). Such mystical thought may readily be identified within the Messianic Scriptures (New Testament) themselves.

The message of Yah'shua (Jesus) that all humanity must "turn" or "repent" (Heb. teshuvah / Gk. metanoéô) and enter the Kingdom of Elohim (God) (cp.Mk.1:14-15) led many of the early Catholics to go one step further, by using the miracles of Messiah and His talmidim (disciples) as 'proof' of spiritual union, to seek some 'special' mystical association with Elohim (God) themselves by means of prolonged meditation or contemplation coupled with various aesthetic practices. Similar ideas have passed into Pentecostalism and charismatic Protestantism viâ the mystical charisma of "tongues of fire" (Ac.2:1-4), likewise bestowed upon those whom Paul baptised in Ephesus (Eph.19:1-7). Mark even identifies specific charisms which were to accompany the talmidim (disciples) as they spread the Besorah (Gospel) message (Mk.16:17-18). But were these mysterious charismata the same as claimed by modern Pentecostals and 'charismatics' or are they counterfeits having more in common with paganism than with New Testament Christianity/Messianism?

A further witness to the spirit of mysticism may be found within the Pauline literature. In 2 Corinthians 12:2-4 the apostle speaks grudgingly about prophecy, visions, dreams, and revelations as a rhetortical foil to the claims of his Corinthian audience. Paul's self-reference to the third person undoubtedly signals his reluctance to focus upon mystical experiences in general. Nowhere does he mention his own conversion, an event dramatically portrayed in Acts 9:1-9. Elsewhere, Paul refers to the living Messiah within his life (Gal.2:20) and explains the Messianic Community (Church) as the Body of Messiah (Rom.12:4-5; 1 Cor.12:27). But these are not descriptive of separate mystical experiences, only clear statements of the continual communion which he feels with the Ruach Mashiach (Spirit of Messiah). While it is true that the Pauline spiritual centre revolves around what is called "the mystery" (Col.1:27), this idea has little in common with contemporary mystery religions. Instead, Paul's mystery is the revelation of Elohim's (God's) plan for human salvation as proclaimed by Messiah Yah'shua (Jesus) and witnessed in the power of the Cross and Resurrection.

Johannine literature also hints at some mystical elements. In the Gospel of John the metaphors of the Good Shepherd (Jn.10:1-18) and of the vine and branches (Jn.15:1-8) serve as possible examples of mystical thought. To these may be added the short oration of Yah'shua (Jesus) concerning His rôle as the bread of life (Jn.6:35-40), a text which has often come to be viewed as a direct comment upon the mystical aspect of the eucharistic celebration of the Master's Supper. Such limited texts, however, even when coupled with the ever present Johannine motif of the close relationship among the Father, Son, and believer, nowhere portray mysticism as an extended activity of the broader Messianic Community (Church). Even the bold testimony of the navi (prophet) at Revelation 1:10 attests only to individual participation in mystical activities.

Whether any of these scriptural examples may actually serve as possible evidence of mysticism in the early Messianic Community (Church) is much debated. And yet it is very clear that the early Messianic (Christian) emunah (faith) was driven by two specific experiences which bore some direct spiritual associations with Messiah:

These were community events which guided individual believers in their spiritual lives and became the foundation of later mystical experiences within Christian history.

Thus, while the evidence is limited and uncertain, the specter of mysticism is clearly evident within early Church consciousness. A broad witness to visions, miracles, and prayers speaks to some broad sense of mystical awareness in the personal life of ancient believers. On the liturgical level, certain authors specifically refer to doctrines and sacraments as 'mysteries' of the common Christian experience (e.g. Ignatius Eph.19.1; Trall.2.3, "deacons of the mysteries of Yah'shua the Messiah (Jesus Christ)"; Didache 11:11, "worldly mystery of the Messianic Community (Church)"). During the 2nd century, the 'peak experience' of mysticism became associated with martyrdom with Messiah (cf.Mart.Pol.15.1-2).

During those early years, certains elements of the Church were greatly influenced by mysticism in Judaism. Jewish speculation, rooted in occultism (that would later evolve into kabbalism), became a dynamic force as it sought to find the heavenly Elohim (God) within the common elements of daily life. Prominent in this quest during the 1st century was Philo of Alexandria, whose philosophy came to argue that the 'spirit' (Gk, pneűma) of Elohim (God) resides in the centre of the human will in the form of the 'mind' (Gk. noús). His ideas influenced Christian speculation in Alexandria and Egyptian aesceticism in general. Philo stands prominently behind the principles of Clement of Alexandria, who insisted upon gnosis (i.e. divine knowledge) as the ultimate goal of the Christian experience, and of Origen, who sought to wed the human soul with the divine Logos (Word) as the ultimate union between the believer and Elohim (God).

The rise of mysticism within patristic literature is most fully evident during the 4th through 6th centuries under the influence of Cappadocian thought. Key among the 4th century authors was Pseudo-Macarius, an Egyptian anchorite (someone withdraws from secular society so as to be able to lead an intensely prayer-oriented, aescetic, or Eucharist-focused life) who spoke of the mystical experience as that point when the soul embraces Elohim (God) and becomes 'a spiritual eye and entirely light'. His contemporary, Evagrius of Pontus, sought mystical union with Elohim (God) through a progression of stages whose culmination in the full knowledge of the trinity brought freedom from all passion, a goal not unlike that sought by Buddhists.

True systematic treatises on Christian mysticism appeared only at the end of the 5th century. Noteworthy here is the Mystical Theology of Pseudo-Dionysus the Areopagite of Syria, as well as The Ladder of Divine Ascent of John Climacus, written as a practical guide for the monastic life. Eastern 'spirituality' ultimately had a great influence upon later Western views of mysticism, as evident from the mystical speculations of Ambrose of Milan and his pupil Augustine of Hippo (cf. his Confessions). To this tradition should be added the names Jerome, Gregory the Great, and Maximus Confessor, to name but a few late patristic voices.

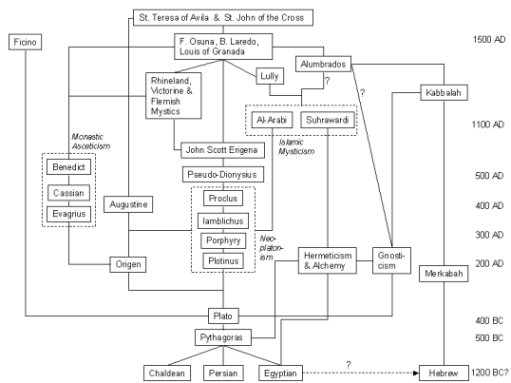

The evolution of mystical schools (bottom to top)

20 September 2018

Comments from Readers

[1] "Mysticism: that which can only be experienced. In this way the 'born again' experience is the height of Christian mysticism" (SH, England, 20 January 2018).

|